Visualizing The World’s Largest Sovereign Wealth Funds

Visualizing the Race for EV Dominance

Saying Bye to Facebook: Why Companies Change Their Name

Visualizing Social Risk in the World’s Top Investment Hubs

Ranked: The Largest Oil and Gas Companies in the World

From Amazon to Zoom: What Happens in an Internet Minute In 2021?

Visualizing the Race for EV Dominance

Saying Bye to Facebook: Why Companies Change Their Name

Mapped: The Fastest (and Slowest) Internet Speeds in the World

Ranked: Big Tech CEO Insider Trading During the First Half of 2021

Ranked: The Best and Worst Pension Plans, by Country

Visualizing The World’s Largest Sovereign Wealth Funds

Visualizing Women’s Economic Rights Around the World

Billionaire Late Bloomers, by Age of Their Breakthrough

The Richest People in Human History, to the Industrial Revolution

Visualizing The Most Widespread Blood Types in Every Country

Pandemic Recovery: Have North American Downtowns Bounced Back?

Ranked: The Most Prescribed Drugs in the U.S.

How Does the COVID Delta Variant Compare?

Visualizing the World’s Biggest Pharmaceutical Companies

Mapped: Solar Power by Country in 2021

Visualizing the Race for EV Dominance

Ranked: The Largest Oil and Gas Companies in the World

The Top 10 Biggest Companies in Brazil

Which Countries Have the Most Nuclear Weapons?

Mapped: Solar Power by Country in 2021

The Top 10 Biggest Companies in Brazil

All the Metals We Mined in One Visualization

Visualizing the Critical Metals in a Smartphone

Silver Through the Ages: The Uses of Silver Over Time

A Deep Dive Into the World’s Oceans, Lakes, and Drill Holes

Mapped: Solar Power by Country in 2021

Visualizing the Race for EV Dominance

Net-Zero Emissions: The Steps Companies and Investors Can Consider

Mapped: Human Impact on the Earth’s Surface

Animation: How the European Map Has Changed Over 2,400 Years

Visualizing Social Risk in the World’s Top Investment Hubs

Interactive Map: Tracking World Hunger and Food Insecurity

Mapped: Where are the World’s Ongoing Conflicts Today?

Which Countries Have the Most Nuclear Weapons?

Published

on

By

As anyone who’s started a company knows, choosing a name is no easy task.

There are many considerations, such as:

The list goes on. These considerations are amplified when a company is already established, and even more difficult when your company serves billions of users around the globe.

Facebook (the parent company, not the social network) has changed its name to Meta, and we’ll examine some probable reasons for the rebrand. But first we’ll look at historical corporate name changes in recent history, exploring the various motivations behind why a company might change its name. Below are some of the categories of rebranding that stand out the most.

Societal perceptions can change fast, and companies do their best to anticipate these changes in advance. Or, if they don’t change in time, their hands might get forced.

As time goes on, companies with more overt negative externalities have come under pressure—particularly in the era of ESG investing. Social pressure was behind the name changes at Total and Philip Morris. In the case of the former, the switch to TotalEnergies was meant to signal the company’s shift beyond oil and gas to include renewable energy.

In some cases, the reason why companies change their name is more subtle. GMAC (General Motors Acceptance Corporation) didn’t want to be associated with subprime lending and the subsequent multi-billion dollar bailout from the U.S. government, and a name change was one way of starting with a “clean slate”. The financial services company rebranded to Ally in 2010.

Brands can become unpopular over time because of scandals, a decline in quality, or countless other reasons. When this happens, a name change can be a way of getting customers to shed those old, negative connotations.

Internet and TV providers rank dead last in customer satisfaction ratings, so it’s no surprise that many have changed their names in recent years.

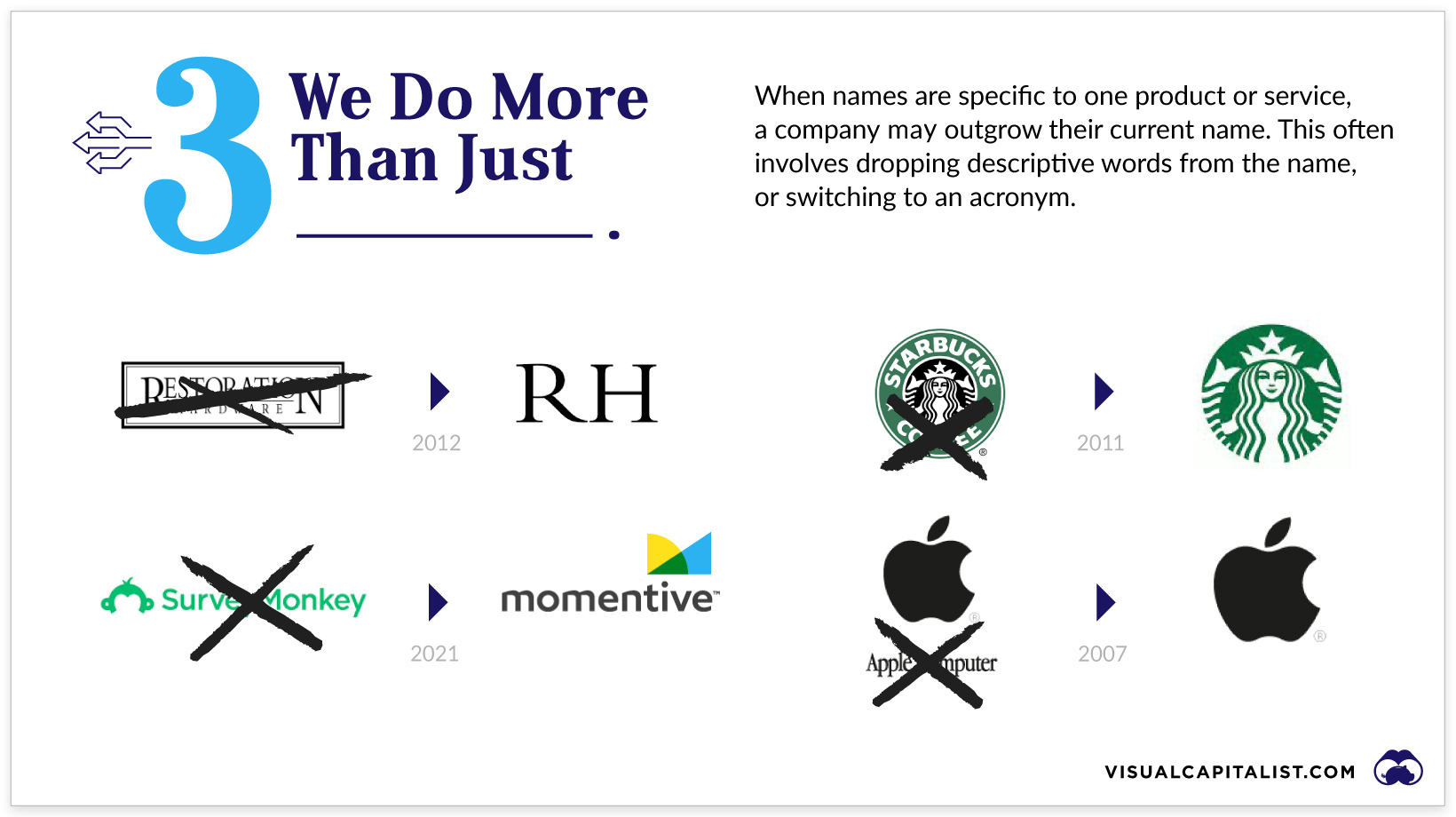

This is a very common scenario, particularly as companies go through a rapid expansion or find success with new product offerings. After a period of sustained growth and change, a company may find that the current name is too limiting or no longer accurately reflects what the company has become.

Both Apple and Starbucks have simplified their company names over the years. The former dropped “Computers” from its name in 2007, and Starbucks dropped “Coffee” from its name in 2011. In both these cases, the name change meant disassociating the company with what initially made them successful, but in both cases it was a gamble that paid off.

One of the biggest name changes in recent years is the switch from Google to Alphabet. This name change signaled the company’s desire to expand beyond internet search and advertising.

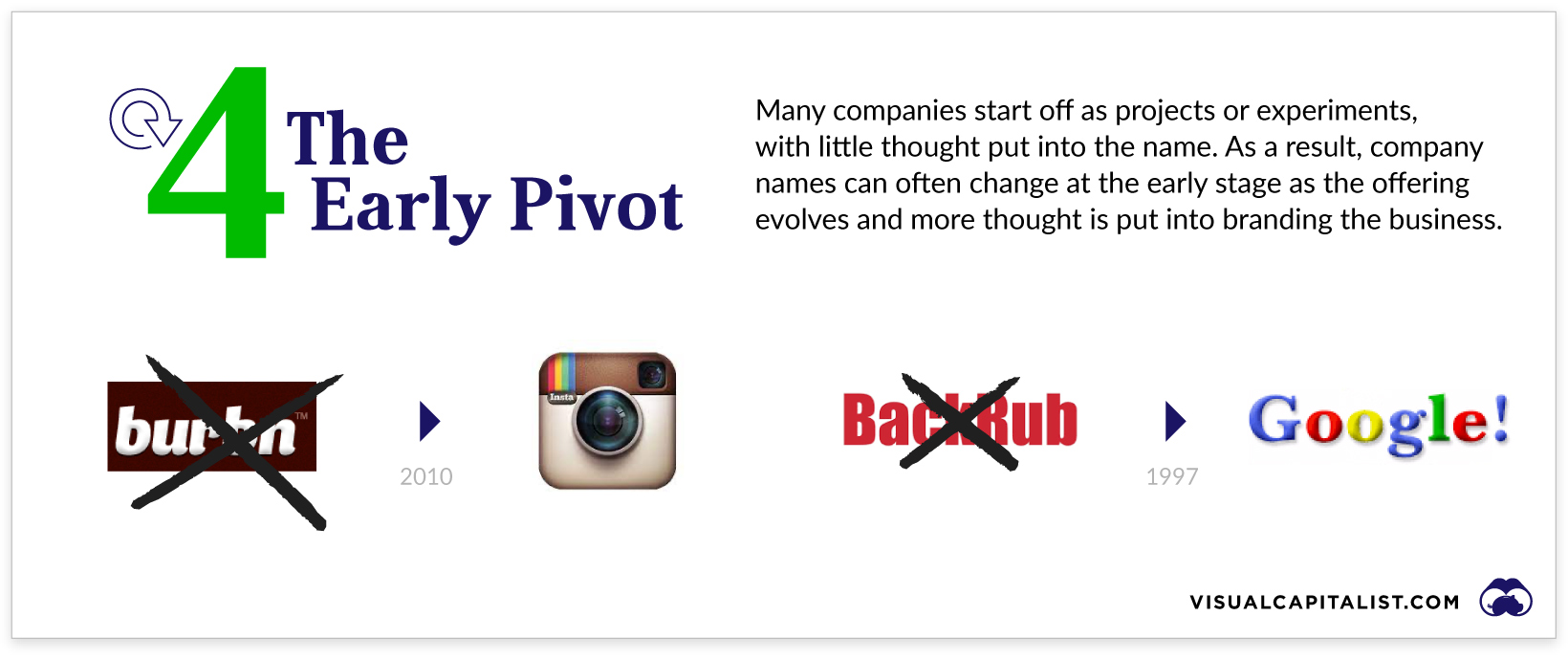

Another very common name change scenario is the early-stage name change.

In the world of music, there’s speculation that limited melodies and subconscious plagiarism will make creating new music increasingly difficult in the future. Similarly, there are millions of companies in the world and only so many short and snappy names. (That’s how we end up with companies called Quibi.)

Many of the popular digital services we use today started with very different names. The Google we know today was once called Backrub. Instagram began life as Bourbn, and Twitter began life as “Twittr” before finding a spare E in the scrabble pile.

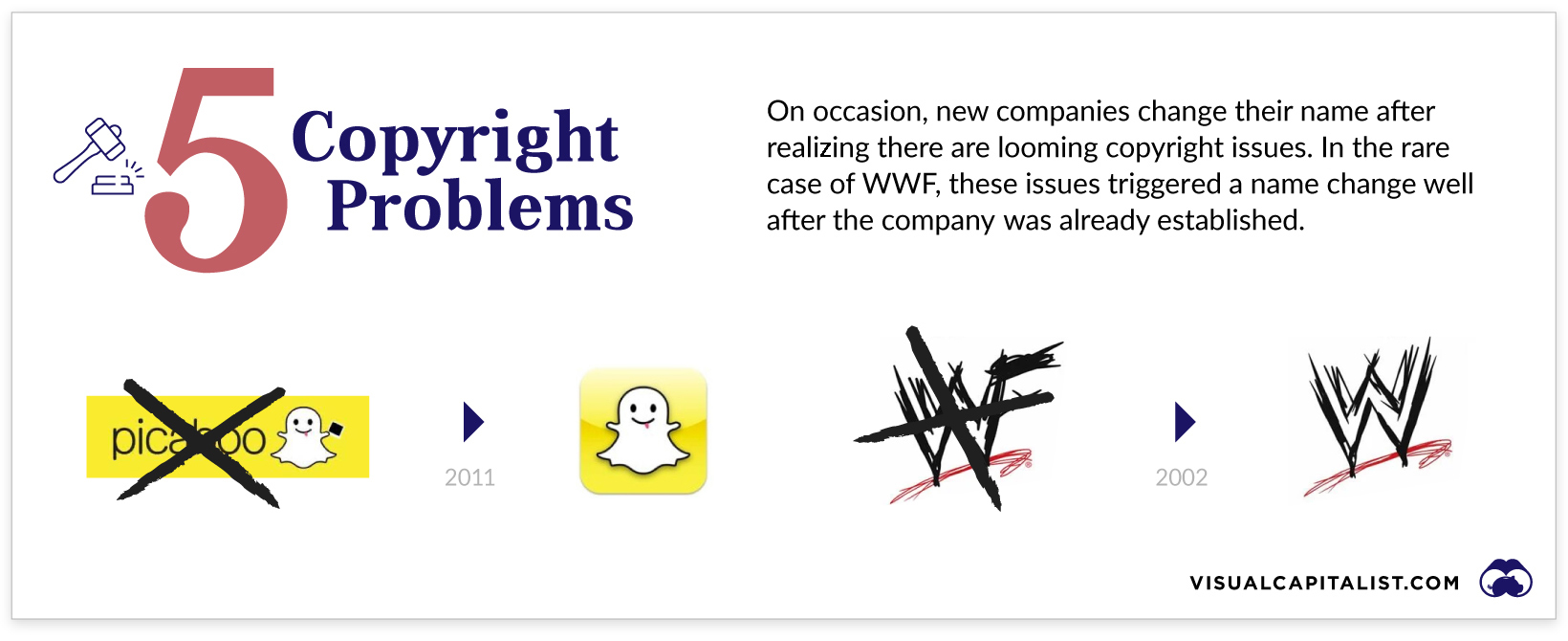

As mentioned above, many companies start out as speculative experiments or passion projects, when a viable, well-vetted name isn’t high on the priority list. As a result, new companies can run into trademark problems.

This was the case when Picaboo, the precursor of Snapchat, was forced to change their name in 2011. The existing Picaboo—a photobook company—was not thrilled to share a name with an app that was primarily associated with sexting at the time.

The fight over the name WWF was a more unique scenario. In 1994, the World Wildlife Fund and the World Wrestling Federation had a mutual agreement that the latter would stop using the initials internationally, except for fleeting uses such as “WWF champion”. In the end though, the agreement was largely ignored, and the issue became a sticking point when the wrestling company registered wwf.com. Eventually, the company rebranded as WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) after losing a lawsuit.

To err is human, and rebranding exercises don’t always hit the mark. When a name change is universally panned or, perhaps worse, not relevant, it’s time to course correct.

Tribune Publishing was forced to backtrack after their name change to Tronc in 2016. The widely-panned name, which was stylized in all lower case, was seen as a clumsy attempt to become a digital-first publisher.

Facebook undertook this name change for a number of reasons, but chief among them is that the brand is irrevocably associated with scandals, negative externalities, and Mark Zuckerberg.

Even before the most recent outage and whistle-blowing scandal, Facebook was already the least-trusted tech company by a long shot. Mark Zuckerberg was once the most admired CEO in Silicon Valley, but has since fallen from grace.

It’s easy to focus on the negative triggers for the impending name change, but there is some substance behind the change as well. For one, Facebook recognizes that privacy issues have put their primary source of revenue at risk. The company’s ad-driven model built upon its users’ data is coming under increasing scrutiny with each passing year.

As well, there is substance behind the metaverse hype. Facebook first signaled their ambitions in 2014, when it acquired the virtual reality headset maker Oculus. A sizable portion of the company’s workforce is already working on making the metaverse concept a reality, and there are plans to hire 10,000 more people in Europe over the next five years.

It remains to be seen whether this immense gamble pays off, but for the near future, Zuckerberg and Facebook’s investors will be keeping a close eye on how the media and public react to the new Meta name and how the transition plays out. After all, there are billions of dollars at stake.

Pandemic Recovery: Have North American Downtowns Bounced Back?

Visualizing Social Risk in the World’s Top Investment Hubs

From Amazon to Zoom: What Happens in an Internet Minute In 2021?

Ranked: The 50 Companies That Use the Highest Percentage of Green Energy

Ranked: Big Tech CEO Insider Trading During the First Half of 2021

The World’s Most Used Apps, by Downstream Traffic

Which Companies Belong to the Elite Trillion-Dollar Club?

Which Country is the Cheapest for Starting a Business?

A lot can happen in an internet minute. This stat-heavy graphic looks at the epic numbers behind the online services billions use every day.

Published

on

By

In our everyday lives, not much may happen in a minute. But when gauging the depth of internet activity occurring all at once, it can be extraordinary. Today, around five billion internet users exist across the globe.

This annual infographic from Domo captures just how much activity is going on in any given minute, and the amount of data being generated by users. To put it mildly, there’s a lot.

At the heart of the world’s digital activity are the everyday services and applications that have become staples in our lives. Collectively, these produce unimaginable quantities of user activity and associated data.

Here are just some of the key figures of what happens in a minute:

As these facts show, Big Tech companies have quite the influence over our lives. That influence is becoming difficult to ignore, and draws increasing media and political attention. And some see this attention as a plausible explanation for why Facebook changed their name—to dissociate from their old one in the process.

One tangible measure of this influence is the massive amount of revenue Big Tech companies bring in. To get a better sense of this, we can look at Big Tech’s revenue generating capabilities on a per-minute basis as well:

Much of the revenue that these elite trillion-dollar stocks generate can be traced back to all the activity on their various networks and platforms.

In other words, the 5.7 million Google searches that occur every minute is the key to their $433,014 in per minute sales.

With the amount of data and information in the digital universe effectively doubling every two years, it’s fair to say the internet minute has gone through some changes over the years. Here are just some areas that have experienced impressive growth:

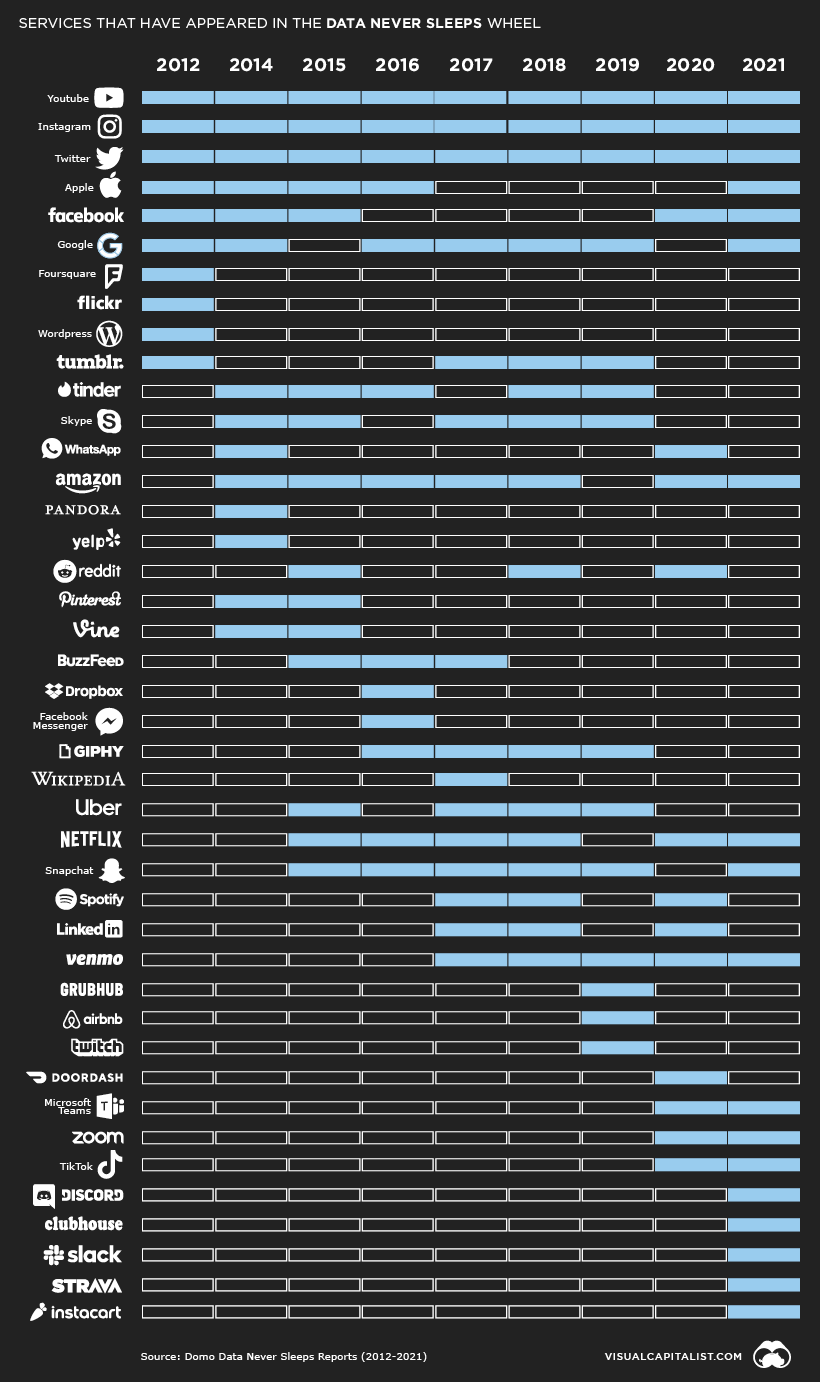

Here’s a look at the services that have been featured in the various iterations of this graphic over the years:

Twitter, Instagram, and Youtube are the only three brands to be featured every single year.

The Internet Minute wheel also helps to put the internet’s rapid rate of adoption into perspective. For instance, in 1993, there were only 14 million internet users across the globe. But today, there are over 14 million just in Chile.

That said, the total addressable market still has some room left. By some measures, the complete number of internet users grew by 500 million in 2021, a roughly 11% jump from 4.5 billion users in 2020. This comes out to an astonishing 950 new users on a per minute basis.

What’s more, in the long term, with the appropriate infrastructure in place, certain areas within emerging markets can experience buoyant growth in the number of connected citizens. Here’s where the next billion internet users may come from, based on the largest disconnected populations.

With this growth trajectory in mind, we can expect future figures to become even more astonishing. But the human mind is known to be bad at interpreting large numbers, so in future editions, the internet minute figures may need to be stripped down to the internet second.

Tesla was the first automaker to hit a $1 trillion market cap, but other electric car companies have plans to unseat the dominant EV maker.

Published

on

By

This was originally posted on Elements. Sign up to the free mailing list to get beautiful visualizations on natural resource megatrends in your email every week.

Tesla has reigned supreme among electric car companies, ever since it first released the Roadster back in 2008.

The California-based company headed by Elon Musk ended 2020 with 23% of the EV market and recently became the first automaker to hit a $1 trillion market capitalization. However, competitors like Volkswagen hope to accelerate their own EV efforts to unseat Musk’s company as the dominant manufacturer.

This graphic based on data from EV Volumes compares Tesla and other top carmakers’ positions today—from an all-electric perspective—and gives market share projections for 2025.

According to Wood Mackenzie, Volkswagen will become the largest manufacturer of EVs before 2030. In order to achieve this, the world’s second-biggest carmaker is in talks with suppliers to secure direct access to the raw materials for batteries.

It also plans to build six battery factories in Europe by 2030 and to invest globally in charging stations. Still, according to EV Volumes projections, by 2025 the German company is forecasted to have only 12% of the market versus Tesla’s 21%.

Other auto giants are following the same track towards EV adoption.

GM, the largest U.S. automaker, wants to stop selling fuel-burning cars by 2035. The company is making a big push into pure electric vehicles, with more than 30 new models expected by 2025.

Meanwhile, Ford expects 40% of its vehicles sold to be electric by the year 2030. The American carmaker has laid out plans to invest tens of billions of dollars in electric and autonomous vehicle efforts in the coming years.

When it comes to electric car company brand awareness in the marketplace, Tesla still surpasses all others. In fact, more than one-fourth of shoppers who are considering an EV said Tesla is their top choice.

“They’ve done a wonderful job at presenting themselves as the innovative leader of electric vehicles and therefore, this is translating high awareness among consumers…”

—Rachelle Petusky, Research at Cox Automotive Mobility Group

Tesla recently surpassed Audi as the fourth-largest luxury car brand in the United States in 2020. It is now just behind BMW, Lexus, and Mercedes-Benz.

BloombergNEF expects annual passenger EV sales to reach 13 million in 2025, 28 million in 2030, and 48 million by 2040, outselling gasoline and diesel models (42 million).

As the EV market continues to grow globally, competitors hope to take a run at Tesla’s lead—or at least stay in the race.

Animation: How the European Map Has Changed Over 2,400 Years

Mapped: Countries by Alcohol Consumption Per Capita

Here are 15 Common Data Fallacies to Avoid

A Deep Dive Into the World’s Oceans, Lakes, and Drill Holes

The Problem With Our Maps

Visualizing The Most Widespread Blood Types in Every Country

The Richest People in Human History, to the Industrial Revolution

Mapped: Second Primary Languages Around the World

Copyright © 2021 Visual Capitalist

19 novembre, 2021

0 Comments

1 category

Category: Non classé